Since 1964, Leif Erikson Day has been celebrated every 9th of October in the United States to honor not only the accomplishments of the man but the important role of Scandinavian immigrants in the history of the United States.

Of course, since Columbus Day is celebrated the second Monday of every October and is recognized as a federal holiday with many government and banking services closed, we’re basically invited to draw comparisons between the men celebrated since they are both hailed as “discoverers” of “America”. Neither was a saint, and neither actually discovered the Americas – Leif clearly was building on earlier sightings by at least one earlier expedition, and Columbus spent time in Iceland prior to his obsession with the western route to Asia, so he likely knew of the Icelanders’ expeditions to the west.

But both men were emblematic of their age and can be seen as prototypes of Americans yet to come. They are inexorably intertwined in the story of the Western Hemisphere and all its many peoples.

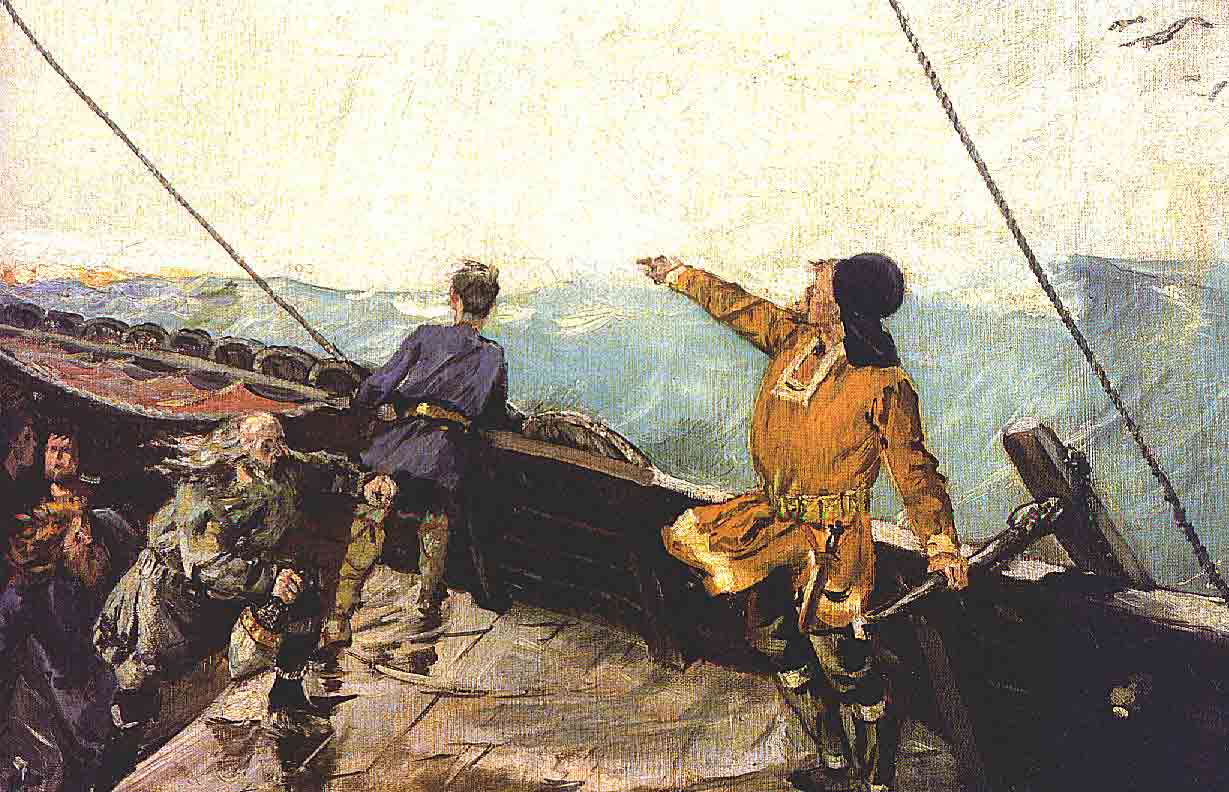

Let’s start with Leif the Lucky.

Leif is called “Erikson” because he was the son of Erik the Red, a well-known explorer during the Viking Age. Born in Norway and eventually exiled from Iceland, Erik chose to sail west rather than return to his ancestral homeland. He ended up making landfall at the island he named “Greenland”, a name he said he gave because people were more likely to settle there if it had a good name. However, it was also the case that the lands in the south of Greenland that Erik was mapping were, in fact, actually covered in vegetation, though today we know the island for its heavy snowfall and massive glaciers. Compared to Iceland, which had its forests completely wiped out within a few decades of colonization, Greenland was an enticing new home for the children of Norway and Iceland.

Erik’s son Leif was born in Iceland around 870 CE, before the expedition to Greenland. The journey on which he discovered North America was a bit more calculated than his father’s trip to Greenland; while Erik had heard tales of lands to the West, nothing had been confirmed and his was a long trip in difficult waters.

Leif had a bit more information for his famous voyage. One summer a sailor named Bjarne made the trip from Iceland to Greenland, but it was his first attempt to meet up with Erik and his fellow settlers, so he had some difficulty making the trip. A storm took him off course and he ended up seeing land that looked nothing at all like the description of Greenland – this land was flat and forested, while Greenland was said to be mountainous and rocky. He kept making his way north and kept finding more land, but none of it matched the description of Greenland. He never came ashore until he worked out the location of Erik’s settlements – further north and a bit to the east.

Once word of Bjarne’s voyage made its way to Leif (and Erik’s other sons), they became greatly excited. They weren’t as excited by discovery for its own sake as they were by Bjarne’s descriptions of massive forests and expansive pastures, lands that could be exploited for great financial gain, especially in Iceland, where timber for building was highly desirable.

While Leif wanted his father to make the expedition, Erik became injured on the journey to the ships, so Leif led the expedition. He found his way to the western lands Bjarne had discovered and navigated three large sections of land, which he called Helluland, Markland, and Vinland. Modern review of the Icelandic sagas compared to our current cartography leads us to believe that Leif scouted out areas that we believe are those we now know as Baffin Island, Labrador, and further down into Canada, especially Newfoundland. Leif and his companions came to build a settlement on the northernmost point of the large island we know as Newfoundland, the construction of which was discussed in the sagas. Perhaps most importantly, this settlement was discovered in the 1960s, confirming decades (even centuries) of speculation* about just how accurate the sagas had depicted the westward journeys of the Norsemen. This settlement, at the site called L’Anse aux Meadows, proves that there were Europeans in North America around 1000 CE. The sagas even record the name of the first European born in North America, Leif’s nephew, named Snorri.

Leif soon returned to Greenland and left the Vinland expedition to his brother Thorvald. He had previously promised Olaf Tryggvason, the King of Norway, that he would work to convert the remaining heathen holdouts in the west. And more pressingly, he was next in line to be chief of the Greenland expedition, and he had to pay attention to all the people who had settled there, not just the settlements in even newer lands.

As you may have heard, North America was not conquered, or settled, or annexed, by the heathen Vikings or the Christian North. All the promise of the lush and fertile settlements at L’Anse aus Meadows and anywhere else the settlers may have landed (speculation based on text from the sagas has led some researchers to surmise the voyages led as far south as Rhode Island and as far west as the Great Lakes) could not be fulfilled without manual labor to accomplish their goals of exploiting those resources. The labor was available – there were plenty of adventurous spirits throughout Iceland and Norway. But the cost was too high. Because these weren’t lands sitting there ripe for the taking. They were already inhabited by skraelingjar (possibly “barbarians”, “shouters”, “weaklings”, the original meaning is unclear)– the aboriginal Inuit and other native tribes who had lived in North America, and in Helluland, Markland, and Vinland specifically, for thousands of years. The Greenlanders had poor relations with the natives, and colonization, even for the purpose of extracting resources, became too costly to maintain.

You probably know Columbus’s story better. Or at least you think you do.

Five hundred years after Leif the Lucky’s first expedition to what we now call North America, Columbus convinced Ferdinand II of Aragon and Isabella I of Castile, King and Queen of Spain, that he could sail west and arrive in Asia. He did not prove that the Earth was spherical as that had long since been proven via mathematics and scientific measurement. In fact, his voyage flew in the face of the advice of every scientist consulted by every monarch and noble he begged for resources. They knew well that the Earth was far too large for such a voyage to be feasible with the technology available at the time.

But Ferdinand, from pity, annoyance, or the hope that even a small chance of success could bring much glory to himself and Spain, funded Columbus’s mission, and in 1492 CE, Columbus sailed west.

Luckily for Columbus, there was a massive continent between Europe and Asia that prevented him from dying of dehydration, starvation, or exposure. He made landfall on an island he named San Salvador (not necessarily the island we call San Salvador), and which had a healthy, and notably non-Asian, native population.

Columbus then went about enslaving that local population, taking several captives back with him to Spain, and preparing a report on tactics for how to conquer them with superior Spanish weaponry. Between agricultural resources, the ability to use the population as slave laborers, and obvious mineral resources such as gold, Columbus saw the land and the people as easily exploitable. And remember that he thought – and went to his grave thinking – that he had landed in Asia, a land he knew to have large populations, substantial cultural traditions dating back hundreds of years and spanning hundreds of kilometers, and even some military dynasties that had conquered significant chunks of Asia itself. Columbus was prepared to go to war with whoever and whatever he found.

This is not to say that Leif, Erik, and their kin were immaculate saints; they belonged to a civilization with a large slave underclass and as ruling citizens, the slaves served them in particular. Erik was exiled from Iceland because of disputes that turned deadly. But in a brutish age, Erik and his children worked for themselves, for their families, for their communities, and for their faith. Columbus sought glory and accolades and cared little for the advice of experts, the well-being of others, or the consequences of his actions.

In the United States, we celebrate Columbus the discoverer when he was in fact a conqueror, convinced he could and should do anything he wanted because he was wealthy and Christian and well-loved by those in power.

But Leif the Lucky and his father Erik the Red are barely remembered, with Leif given a day of celebration in the shadow of a national holiday for Columbus the Conqueror.

And the issue isn’t just about how well the men are remembered or what gets taught in schools. Leif is an important transitional figure for who the Northern European peoples were and who they would become. As a convert from the Old Way to Christianity, Leif was part of a generation that changed how Iceland in particular, and Scandinavia in general saw itself. While conversion had been taking place here and there for centuries, Leif’s conversion, and his efforts in Iceland and Greenland, were part of one of the biggest efforts in the history of the Christian mission to the North. Scandinavia was changing the way it saw itself. More than ever, the Viking raids were ending, religious conflict was coming to an end, and those who kept to the Old Way did so quietly. Perhaps the most important turning point was the decision at the Icelandic national assembly in 1000 CE that the whole country should convert rather than continue in strife. Leif, born a heathen to a father who held to the Old Way until he died, is a powerful symbol of this transition and the way it was managed peacefully.

Columbus, on the other hand, brought slavery, murder, and exploitation in the name of egotism and bastardized Christianity wherever he stepped.

So tomorrow, October 9th, remember Leif Erikson, his father Erik the Red, and the Norse folk who closed out the Viking Age. They were far different from us and lived in a violent, brutish age. Whether they made their compromises from honest religious conviction, or in following the correct, righteous religious path, is beyond my capacity for knowledge. Perhaps they were right or perhaps they made terrible mistakes.

But their spirit of exploration, adventure, and consideration of costs in the service of profit that benefits all – those are values that are worth remembering as we look back on decisions that have profoundly affected the lives of nearly a billion people living on these two continents today. Even if we don’t – and shouldn’t – forget the other guy, maybe we should work a little harder to remember what was going on at the turn of the last millennium in the North.

* One of the authors (Arthur Middleton Reeves) of the book linked here appears to be a distant cousin of mine.

Thoughtful and interesting piece. It is strange, logically I know these two men lived centuries apart, but in the imagery of my thoughts, they are contemporaries, grouped together in the “way back when”. Odd how the mind works. Thank you for making my image a bit clearer.

LikeLiked by 1 person

[…] sagas became more widespread, so, too, did interest in just how accurate their depictions of trips west of Greenland were. Immigrants to the United States were not merely from the British Isles (though of course […]

LikeLike

[…] But as we’ve discussed in this space before, Columbus’s other claim to fame, discovering North America, was also accomplished by someone else. […]

LikeLike

[…] tale of ancient Germanic peoples taking their culture and beliefs abroad. We’ve talked about Vinland, but we’ll get to other stories like the Varangian Guard in Byzantium another […]

LikeLike

[…] If you want to read up on the Vikings’ brief settlement of North America, I’ve got a decent post about that for […]

LikeLike